Numerous theories and lots of research expound upon the importance of artistic expression. For young children and adolescents, art is an especially crucial form of personal expression. Children need to experience their own process rather than to produce a piece that someone else wants. At Wheaton Montessori, we also are sensitive to different expressive needs throughout different stages of development.

Process vs. Product

For our youngest students, the process of making art is much more important than the product. When infants and toddlers are engaged in art activities, they are expressing feelings that they may not yet have words or abilities to express. During these early years, we focus on offering young children a variety of different artistic mediums and model how to use them and how to clean them up.

Use of Tools

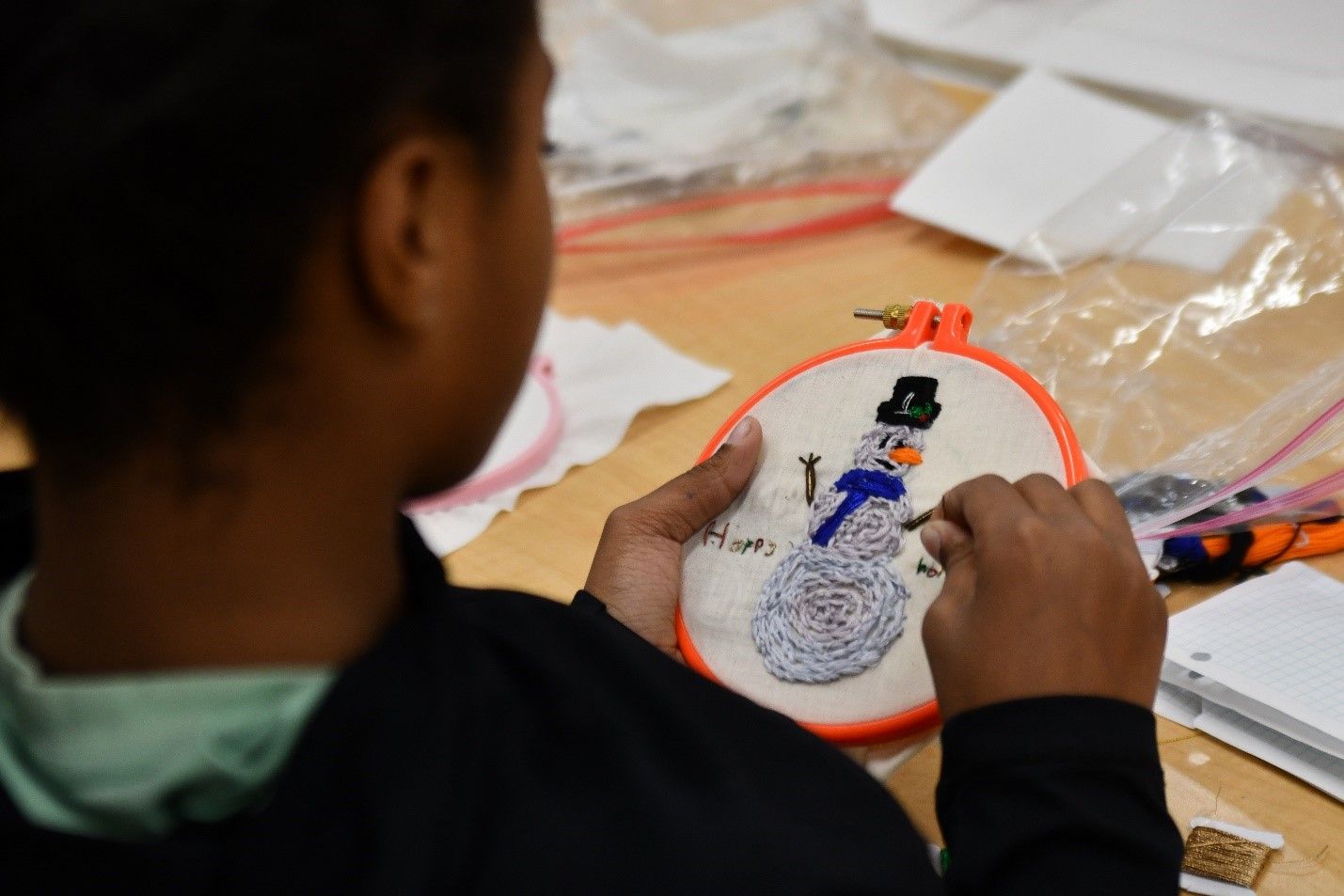

Each teacher sits beside our young children one at a time to show young children how to use different tools. We show how to use just a little water and the tip of the brush with watercolor paints. We explore different techniques with crayons. In elementary we also introduce various fiber art tools–like knitting needles, crochet hooks, or looms.

We also open up a range of possibilities for children to explore. For example, in introducing clay, we show how to carefully get out the clay, how to use different techniques such as forming coils and slabs, how to cut, carve, or roll the clay, and how to store it when finished. We may also show examples of clay sculptures, whether in books or museums. With all of this information, children have a range of inspiration when they decide to work with clay.

Adult Response

To support young children’s artistic expression, we offer objective comments: “Oh how interesting…the lines go up and down,” or “I can see you used a lot of red and blue paint today.” We want to be very careful, so we don’t give any indication of judgment, either good or bad. Young children do not yet have the language to explain their art. Therefore, we want to make sure our comments don’t inadvertently create expectations for children.

At Wheaton Montessori, adults don’t insist that children express themselves artistically, or tell children what or when to do so. We keep inviting students so that they feel inspired and invited to creative. Children’s artwork is individual, creative, non-competitive, and often connected to other subjects. We don’t expect children to learn to imitate adult creations or turn out products that all look alike.

Into the Elementary Years

Art in our elementary classroom is often connected to students' intellectual pursuits. When studying Ancient Egypt, students may want to create a portrait in profile or a model of a pyramid. If they are immersed in learning about a country, they might learn about the symbolism of the flag’s colors and sew a sample flag.

All of this work is aided by the fact that children of this age love big projects. To support their artistic and intellectual pursuits, we provide elementary students with all kinds of studio supplies so they can access the materials they need to create big projects and share their learning with their peers.

Through Adolescence

During adolescence, young people need even more opportunities to form, shape, express, and clarify their inner thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Artistic expression can be a vital outlet during this turbulent time, and can allow adolescents to not only reach a better understanding of who they are but also to be able to connect deeply with others through shared expression.

Adolescents benefit in many ways from creative expression. They can explore questions of identity and their place within social groups and society. Adolescents need creative outlets to keep their spirits vibrant and explore deeper questions. In addition, expressive opportunities allow adolescents to merge their emotions with their intellect.

Vital Form of Expression

At Wheaton Montessori, we feel strongly that young people need artistic outlets so they can have balance in their physical, emotional, social, intellectual, spiritual, and creative development. Our school supports the development of the whole person including their personal creativity.

Art is a vital form of expression throughout different stages of growth. Through art children can express what they are feeling, elementary-age students can integrate their learning and refine their skills, and adolescents can better understand themselves and their connections to others. Creating art can allow our young people to reveal feelings that they could perhaps not express in words. We offer children a variety of art mediums and different experiences, as well as the freedom to choose and experience the form they have chosen.

As always, we invite you to come to visit our school to see this artistic expression in action. Contact the office to observe an Adolescent seminar or to observe your younger child’s school day. If you have a young toddler or preschooler and haven’t found your family’s school yet, please take schedule a tour here to see our artistic students working side by side with other friends. We currently are enrolling twos, threes, and fours to begin in the summer and fall. Unfortunately, our kindergarten though 9th grade waitlist is closed.